Take a look at the people around you. Do you see anyone who doesn’t own a smartphone? Do you know anyone who doesn’t have access to an internet-enabled device? In all parts of the world, more and more people have access to online systems. It’s perhaps not even necessary to quote the actual metrics, but just for the record, there were nearly 4.38 billion users as of March 2019.

The relevant population for clinical trials is well-connected and using a variety of devices

To most people, it would seem obvious that clinical trial participants who must report information and use an electronic diary would be able to do so using the devices they already own and are accustomed to using in a “Bring Your Own Device” (BYOD) setting. This would save trial sponsors money as they don’t need to purchase devices and SIM cards or handle the logistics of getting a device to a patient and then retrieve it. It would also eliminate the extra burden from the sites, who wouldn’t need to maintain the hardware and train patients to use them. For patients themselves, they wouldn’t need to learn to use a new device, which they must also keep charged and carry along with their own devices. Patients might also prefer to use one of the other devices they own, depending on the situation. A lot of people spend a significant amount of time on their laptops during the day in the office, but rely more on mobile devices when on the move. Having this flexibility is likely to reduce the burden on patients and increase their compliance with data entry requirements of the study.

A typical clinical trial experience might feel like this from the patient’s perspective. We CAN and SHOULD simplify this

Concerns about BYOD

So with these numerous benefits, why are we not relying more on the devices patients already have access to in clinical trials? The often-quoted reason relates to concerns regarding eCOA instrument (questionnaires, diaries) validation when a particular instrument is used across many different types of devices. How can we make sure a particular questionnaire displays and behaves as expected, whether it’s displayed on a smartphone, tablet, or a desktop computer? How do we provide the evidence that a particular questionnaire is fit for its intended use if we can’t control the device it runs on? The regulators haven’t actually given clear expectations regarding this. The FDA has merely stated that “additional evidence” is required when paper instruments are migrated to electronic formats. They also say that this doesn’t mean that companies need to conduct extensive validation studies to prove the adequacy of the electronic migration.

There are some clever tricks that can be done to ensure a suitable user experience across many device types

The other challenges with BYOD are the perceived operational/technology challenges. Despite the high number of people having access, not everyone still has a suitable device. Users also typically have full administrative access to their devices, including the ability to turn off in-app notifications from the device settings or even deleting the entire app. Users may also of course be replacing their devices in the middle of the study, which would require re-installation of any study specific apps. While these are valid concerns, they can all be addressed as part of the overall solution.

Paper to electronic migration

While the above are the most talked-about concerns that have to do with BYOD eCOA, there is one very significant factor that is far less talked about. That is the design aspect of the eCOA solution itself, including all of the surrounding elements of the solution. When a paper instrument is migrated to electronic format, it will always change to a greater or lesser degree. Electronic diaries will behave differently because we’re talking about a very different type of user interface, usually a touch-screen device rather than pen and paper. In addition to the obvious changes related to that, electronic diaries often add things that did not exist on paper, for example:

- Alarms and reminders

- Time windows, for example to only allow data entry in the morning

- Navigation

- Scrolling

- Edit checks

- Automatic calculations

- Audit trails and the ability to allow/restrict backfilling missed entries up to a certain point

- Security mechanisms, such as logging in via PIN or username and password

- Workflows, such as tracking an ongoing event to its completion, asking questions related to a measurement from a biometer, etc.

In most cases, when companies conduct usability testing and cognitive interviewing they completely ignore the above items and only focus on the questionnaire itself to make sure the patient is able to understand the questions and make a response. Also, perhaps surprisingly, the objective of typical usability testing in this setting is not to get input to optimize usability, but rather to confirm that the current design allows patients to complete entries on the form in a rather artificial setting.

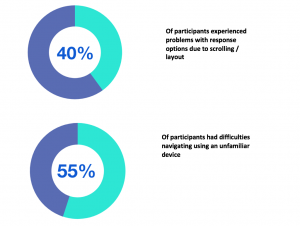

In a recent usability study1 conducted by eClinicalHealth and partners, focusing on BYOD with participants aged 60+ who own at least one Internet-enabled device:

Largely because of this suboptimal process, BYOD is little used in clinical trials, with both patients and sponsors missing out on the benefits. It’s time that we changed that.

iUsability

I have been working with this particular issue for nearly a decade and we have released an updated process that addresses the above concerns. This new process is called iUsability, which stands for “Integrated Usability” and means that the eCOA designer(s) and the usability research team work as a tightly integrated team. The traditional process where everything is tested at the end is turned around; and the testing, patient input, and usability optimization is actually done at the very beginning.

iUsability process

The first step in the process is for the designer to perform the migration from paper to electronic format – ideally doing this taking BYOD into account. This quite often leads to situations where the designer may not be sure of the best possible design for a particular instrument and patient population. For example, the design team might not be sure if patients would prefer a more efficient table layout where a number of similar questions are presented in a table format as they usually are on paper, or a more consistent single question per page format, which would require many more clicks to complete, but would behave the same way on all devices. This might have an impact on the patient burden, as clicking through several screens might be OK for a single questionnaire, but what if there are ten others as well?

The designer would also likely add new things that were not part of the original paper instrument, such as the alarms and edit checks mentioned earlier. They might also need to adjust the instructions, because patients are no longer “ticking a box”, but rather “selecting an item”. They key is for the designer to do the best job possible to ensure the instrument behaves well across all devices and appropriately documents all of this, including any concerns or alternative design options. This document serves as input for the usability research team to design their protocol and interview guide to observe and interview patients to collect patient input regarding these matters. The results from the interviews and the observations from the interviewer are once again documented and fed back to the designer, who can adjust the design and finalize the migration.

The outcome of this process can then include a standardized guideline about how a particular instrument needs to behave in its electronic format in a BYOD setting. This would need to be a rather generic document, so that it can be applied across different devices and even different vendors. Then, no matter which device or vendor is used, there would be far better consistency between different implementations and vendors, so sponsor companies wouldn’t have to repeat this process for every study, device, and vendor they use. The guideline states things like “The instructions including the recall period must be visible on the screen at all times when the patient is making entries.”. This particular requirement can be implemented in several ways, for example by having a mechanism to ensure the instructions remain visible on the screen despite the window being scrolled up or down, or by implementing a single-question layout and copying the instructions on every page.

This process addresses the key elements of enabling BYOD:

- 1. Optimizes the overall usability of the entire solution required for patients (logging in, navigation, data entry, reminders, etc.)

- 2. Provides additional evidence that a particular instrument works and behaves appropriately across a range of suitable devices

- 3. Only needs to be done once for each instrument, and the resulting design guidelines can be shared with the copyright holders for other vendors and companies to use

We have collaborated with industry thought leaders and have used this process very successfully over the past five years and look forward to supporting more and more projects to harness the benefits of BYOD in their clinical trials. Overall, the design-driven process that utilizes patient/user input early in the design process can be highly valuable in optimizing the solution usability and in ensuring it will perform as expected in real-world use. While the most common use case for this process is eCOA migrations, the same process can be applied to any other solution as well, such as patient recruitment, eConsent, patient engagement/retention.

For more information, you can download our service fact sheet here, or reach out to me directly on LinkedIn or by email.